Intro: There are all sorts of guides that explain how to interface a PS2 controller already out there. The goal here is to consolidate the information and make it as fast as possible to get up and running. Please let us know about mistakes!

Update: Check out the arduino ps2 library that Bill Porter helped polish.

Contents:

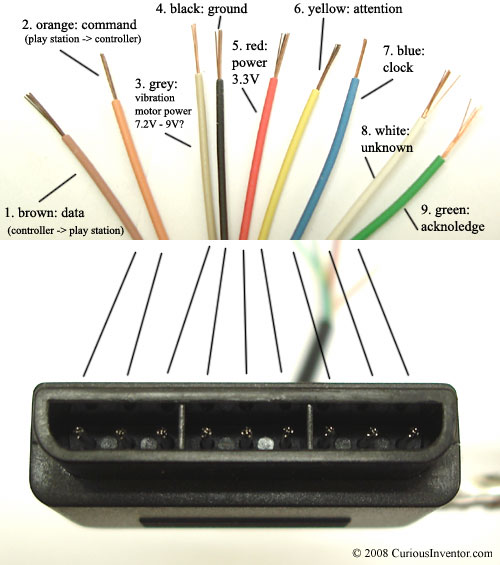

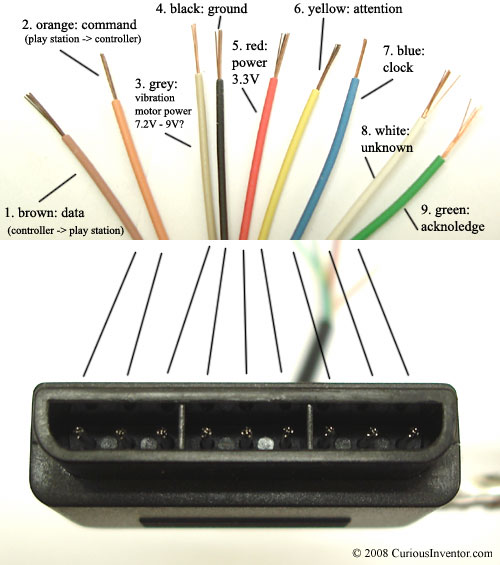

Hardware Interface / Wiring Connections:

Wire Colors and Functionality: There are 9 wires, 6 wires are needed at a minimum to talk to the controller: (clock, data, command, power & ground, attention). To operate vibration motors, motor_power is also needed.

- Brown – Data: Controller -> PlayStation. This is an open collector output and requires a pull-up resistor (1 to 10k, maybe more). (A pull-up resistor is needed because the controller can only connect this line to ground; it can’t actually put voltage on the line).

- Orange – Command: PlayStation -> Controller.

- Grey – Vibration Motors Power: 6-9V? With no controller connected, this meausures about 7.9V, with a controller, 7.6V, most websites say this is 9V (except playstation.txt -> 7.6V), although it will still drive the motors down around 4V, although somewhat slower. When the motors are first engaged, almost 500mA is drawn on this line, and at steady state full power, ~300mA is drawn.

- Black – Ground

- Red – Power: Many sites label this as 5V, and while this may be true for Play Station 1 controllers, we found several wireless brands that would only work at 3.3V. Every controller tested worked at 3.3V, and the actual voltage measured on a live Playstation talking to a controller was 3.4V. McCubbin says that any official Sony controller should work from 3-5V. Most sites say there is a 750mA fuse for both controllers and memory cards, although this may only apply to PS1’s since 4 dual shock controllers could exceed that easily.

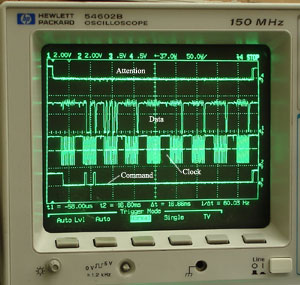

- Yellow – Attention: This line must be pulled low before each group of bytes is sent / received, and then set high again afterwards. In our testing, it wasn’t sufficient to tie this permanently low–it had to be driven down and up around each set. Digitan considers this a “Chip Select” or “Slave Select” line that is used to address different controllers on the same bus.

- Blue – Clock: 500kH/z, normally high on. The communication appears to be SPI bus. We’ve gotten it to work from less than 100kHz up through 500kHz (500k bits / second, not counting delays between bytes and packets). When the guitar hero controller is connected, the clock rate is 250kHz, which is also the rate the playstation 1 uses.

- White – Unknown

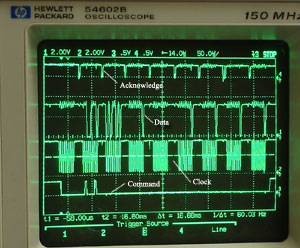

- Green – Acknowledge: This normally high line drops low about 12us after each byte for half a clock cycle, but not after the last bit in a set. This is a open collector output and requires a pull-up resistor (1 to 10k, maybe more). playstation.txt says that the playstation will consider the controller missing if the ack signal (> 2us) doesn’t come within 100us.

Low-Level – How Bytes and Packets are Transferred:

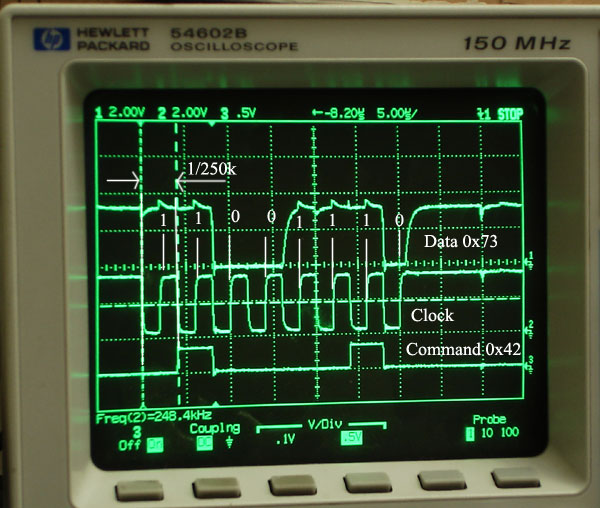

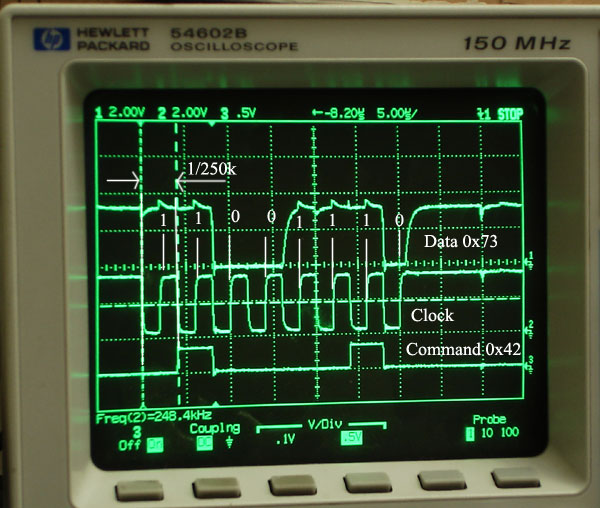

The play station sends a byte at the same time as it receives one (full duplex) via serial communication. The following pictures show actual signals between a playstation and guitar hero controller configured in analog mode (wammy bar sends back 7-bit value (0x7f – 0x00)).

The clock is held high until a byte is to be sent. It then drops low (active low) to start 8 cylces during which data is simultaneously sent and received. When the clock edge drops low, the values on the line start to change. When the clock goes from low to high, value are actually read. Bytes are transferred LSB (least significant bit) first, so the bits on the left (earlier in time) are less significant.

Scope shots showing the acknowledge and attention lines.

High-level: Packet structure, Command and Data Meanings:

Much of this section is sourced from Dowty’s consolidation and home-brew port sniffer and emulator.

Packets have a three byte header followed by an additional 2, 6 or 18 bytes of additional command and controller data (like button states, vibration motor commands, button pressures, etc.).

An example exchange that from a dual shock controller when first plugged in:

Controller defaults to digital mode and only transmits the on / off status of the buttons in the 4th and 5th byte. No joystick data, pressure or vibration control capabilities.

(no buttons pressed)

| byte # |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| Command |

0x01 |

0x42 |

0x00 |

0x00 |

0x00 |

| Data |

0xFF |

0x41 |

0x5A |

0xFF |

0xFF |

Explanation:

— Header: (always the first three bytes)

| byte # |

source /

type |

example

value |

explanation |

| 1st byte |

Command |

0x01 |

New packets always start with 0x01 … 0x81 for memory card? |

| Data |

0xFF |

always 0xFF |

| 2nd byte |

Command |

0x42 |

Main command: can either poll controller or configure it.

See below for command listing |

| Data |

0x41 |

Device Mode: the high nibble (4) indicates the mode (0x4 is digital, 0x7 is analog, 0xF config / escape?),

(lynxmotion calls 0xF ‘DS Native Mode’… not sure)

the lower nibble (1) is how many 16 bit words follow the header,

although the playstation doesn’t always wait for all these bytes |

| 3rd byte |

Command |

0x00 |

Always 0x00 |

| Data |

0x5A |

Always 0x5A, this value appears in several non-functional places |

— Command / Mode Dependent Data (2 to 18 more bytes depending on mode):

| 4th byte |

Command |

0x00 |

Can be configured to control either of the motors |

| Data |

0xFF |

Each digital (on/off) button state is mapped to one of the bits in the 4th and 5th byte |

| 5th byte |

Command |

0x00 |

Can be configured to control either of the motors |

| Data |

0xFF |

1, or all 1’s (0xFF) means everything is unpressed. |

Digital Button State Mapping (which bits of bytes 4 & 5 goes to which button):

| button |

Select |

L3 (jush push) |

R3 |

Start |

Up |

Right |

Down |

Left |

L2 |

R2 |

L1 |

R1 |

Triangle |

O |

X |

Square |

| byte.bit |

4.0 |

4.1 |

4.2 |

4.3 |

4.4 |

4.5 |

4.6 |

4.7 |

5.0 |

5.1 |

5.2 |

5.3 |

5.4 |

5.5 |

5.6 |

5.7 |

For example:

Guitar Hero Button Mapping

| button |

Green |

Red |

Yellow |

Blue |

Orange |

Up |

Down |

Select |

Start |

Wammy |

| byte.bit |

5.1 |

5.5 |

5.4 |

5.6 |

5.7 |

4.4 |

4.6 |

4.0 |

4.3 |

byte 9: 0x7f (released) to 0x00 (pressed) |

- Bytes 4, 6, 7, 8 and 9 are normally 0x7F if nothing is pressed.

Command Listing / Examples:

The most comprehensive listings that we’ve found are Dowty’s and lynxmotion’s. This listing is based on information from both that has been tested.

— 0x41: Find out what buttons are included in poll responses.

The controller can be configured (through command 0x4F) to respond with more or less information about each button with each poll. Only works when the controller is already in configuration mode (0xF3)… use Command 0x43 to enter / exit configuration mode.

| byte # |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

| Command |

0x01 |

0x41 |

0x00 |

0x5A |

0x5A |

0x5A |

0x5A |

0x5A |

0x5A |

| Data |

0xFF |

0x41 |

0x5A |

0xFF |

0xFF |

0x03 |

0x00 |

0x00 |

0x5A |

| section |

header |

bits corresponding to buttons in response packet |

- 18 total bytes can be turned on or off, including the 2 digital state bytes and 16 analog bytes (pressures and joysticks).

- 9.cmd and 9.dat are always 0x5a.

- Data is all 0x00 if controller is in digital mode (0x41)

- Command data is always 0x5A, although 0x00 yields the same result.

— 0x42: Main polling command

Depending on the controller’s configuration, this command can get all the digital and analog button states, as well as control the vibration motors.

| byte # |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

21 |

| Command (hex) |

01 |

42 |

00 |

WW |

YY |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

| Data (hex) |

FF |

79 |

5A |

FF |

FF |

7F |

7F |

7F |

7F |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

| section |

header |

digital |

analog joy |

button pressures (0xFF = fully pressed) |

| analog map |

|

RX |

RY |

LX |

LY |

R |

L |

U |

D |

Tri |

O |

X |

Sqr |

L1 |

R1 |

L2 |

R2 |

- If mode (2.data) is 41, the packet only contains 5 bytes, if mode == 0x73, 9 bytes are returned.

- WW and YY are used to control the motors (which does what depends on the config).

— 0x43: Enter / Exit Config Mode, also poll all button states, joysticks and pressures

This can poll the controller like 0x42, but if the first command byte is 1, it has the effect of entering config mode (0xF3), in which the packet response can be configured. If the current mode is 0x41, this command only needs to be 5 bytes long. Once in config / escape mode, 0x43 does not return button states anymore, but 0x42 still does (except for pressures). Also, all packets have will 6 bytes of command / data after the header.

| byte # |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

21 |

| Command (hex) |

01 |

43 |

00 |

0x01 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

| Data (hex) |

FF |

79 |

5A |

FF |

FF |

7F |

7F |

7F |

7F |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

| section |

header |

digital |

analog joy |

button pressures (0xFF = fully pressed) |

| analog map |

|

RX |

RY |

LX |

LY |

R |

L |

U |

D |

Tri |

O |

X |

Sqr |

L1 |

R1 |

L2 |

R2 |

- 4.command = 0x01 enters config mode (or ‘escape’ mode at Dowty calls it)., 0x00 exits. If 0x00 and already out of config mode, it behaves just like 0x42, but without vibration motor control.

— 0x44: Switch modes between digital and analog

Only works after the controller is in config mode (0xF3).

| byte # |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

| Command (hex) |

01 |

44 |

00 |

0x01 |

0x03 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

| Data (hex) |

FF |

F3 |

5A |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

| section |

header |

config parameters |

- Set analog mode: 4.command = 0x01, set digital mode: 4.command = 0x00

- If 5.command is 0x03, the controller is locked, otherwise the user can change from analog to digital mode using the analog button on the controller. Note that if the controller is already setup to deliver pressure values, toggling the state with the controller button will revert the controller back into not sending pressures.

- Some controllers have a watch-dog timer that reverts back into digital mode if a command is not received within a second or so.

— 0x45: Get more status info

Only works after the controller is in config mode (0xF3).

| byte # |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

| Command (hex) |

01 |

45 |

00 |

5A |

5A |

5A |

5A |

5A |

5A |

| Data (hex) |

FF |

F3 |

5A |

03 |

02 |

01 |

02 |

01 |

00 |

| section |

header |

config parameters |

- 4.data = 0x03 for dual shock controller, 0x01 for guitar hero

- 6.data = 0x01 when LED is on, 0x00 when it’s off

— 0x46: Read an unknown constant value from controller

This command is always issued twice in a row, and appears to be retrieving a 10 byte constant of over those two calls. It is always called in a sequence of 0x46 0x46 0x47 0x4C 0x4C. Only works after the controller is in config mode (0xF3).

| byte # |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

| Command (hex) |

01 |

46 |

00 |

00 |

5A |

5A |

A |

5A |

5A |

| Data (hex) |

FF |

F3 |

5A |

00 |

00 |

00 |

02 |

00 |

0A |

| section |

header |

config parameters |

second pass

| byte # |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

| Command (hex) |

01 |

46 |

00 |

01 |

5A |

5A |

A |

5A |

5A |

| Data (hex) |

FF |

F3 |

5A |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

14 |

| section |

header |

config parameters |

- 4.command appears to get the first half of the constant when it’s 0x00, and the 2nd half when it’s 0x01.

- As shown above, the constant returned for a dual shock controller is: 00 00 02 00 0A 00 00 00 00 14

- A Katana wireless controller and the guitar hero controller each returned this: 00 01 02 00 0A 00 01 01 01 14

— 0x47: Read an unknown constant value from controller

It is always called in a command sequence of 0x46 0x46 0x47 0x4C 0x4C. Only works after the controller is in config mode (0xF3).

| byte # |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

| Command (hex) |

01 |

47 |

00 |

00 |

5A |

5A |

A |

5A |

5A |

| Data (hex) |

FF |

F3 |

5A |

00 |

00 |

02 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

| section |

header |

config parameters |

- Dowty thinks the first byte is probably an offset like in 0x46 and 0x4C, which would leave 5 bytes of interest.

- As shown above, the constant returned for a dual shock controller is: 00 02 00 00 00

- guitar hero controller and Katana wireless: 00 02 00 01 00

— 0x4C: Read an unknown constant value from controller

This command is always issued twice in a row, and appears to be retrieving a 10 byte constant of over those two calls. It is always called in a command sequence of 0x46 0x46 0x47 0x4C 0x4C. Only works after the controller is in config mode (0xF3).

| byte # |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

| Command (hex) |

01 |

4C |

00 |

00 |

5A |

5A |

A |

5A |

5A |

| Data (hex) |

FF |

F3 |

5A |

00 |

00 |

00 |

04 |

00 |

00 |

| section |

header |

config parameters |

second pass

| byte # |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

| Command (hex) |

01 |

4C |

00 |

01 |

5A |

5A |

A |

5A |

5A |

| Data (hex) |

FF |

F3 |

5A |

00 |

00 |

00 |

06 |

00 |

00 |

| section |

header |

config parameters |

- 4.command appears to get the first half of the constant when it’s 0x00, and the 2nd half when it’s 0x01.

- As shown above, the constant returned for a dual shock controller is: 00 00 04 00 00 00 00 06 00 00

- A Katana wireless controller and the guitar hero controller each returned this: 00 00 04 00 00 00 00 07 00 00

— 0x4D: Map bytes in the 0x42 command to actuate the vibration motors

Only works after the controller is in config mode (0xF3).

| byte # |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

| Command (hex) |

01 |

4D |

00 |

00 |

01 |

FF |

FF |

FF |

FF |

| Data (hex) |

FF |

F3 |

5A |

00 |

01 |

FF |

FF |

FF |

FF |

| section |

header |

config parameters |

- 0x00 maps the corresponding byte in 0x42 to control the small motor. A 0xFF in the 0x42 command will turn it on, all other values turn it off.

- 0x01 maps the corresponding byte in 0x42 to control the large motor. The power delivered to the large motor is then set from 0x00 to 0xFF in 0x42. 0x40 was the smallest value that would actually make the motor spin for us.

- 0xFF disables, and is the default value when the controller is first connected. The data bytes just report the current mapping.

- Things don’t always work if more than one command byte is mapped to a motor.

— 0x4F: Add or remove analog response bytes from the main polling command (0x42)

This could set up the controller to only reply with the L1 and R1 pressures for instance. Only works after the controller is in config mode (0xF3).

| byte # |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

| Command (hex) |

01 |

4F |

00 |

FF |

FF |

03 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

| Data (hex) |

FF |

F3 |

5A |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

5A |

| section |

header |

config parameters |

- Each of the 18 bits in FF FF 03 correspond to a response byte, starting with the digital states, then 4 analog joysticks, then 12 pressure bytes.

- By default, the pressure values are not sent back, so this is the command that is necessary to enable them.

Byte Sequence to Configure Controller for Analog Mode + Button Pressure + Vibration Control

The following sequence will setup a controller to send back all available analog values, and also map the left and right motors to command bytes 4 and 5.

— 0x42 Poll once just for fun

| byte # |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| Command (hex) |

01 |

42 |

00 |

FF |

FF |

| Data (hex) |

FF |

41 |

5A |

FF |

FF |

| section |

header |

digital |

— 0x43 Go into configuration mode

| byte # |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| Command (hex) |

01 |

43 |

00 |

0x01 |

00 |

| Data (hex) |

FF |

41 |

5A |

FF |

FF |

| section |

header |

digital |

— 0x44 Turn on analog mode

| byte # |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

| Command (hex) |

01 |

44 |

00 |

0x01 |

0x03 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

| Data (hex) |

FF |

F3 |

5A |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

| section |

header |

config parameters |

— 0x4D Setup motor command mapping

| byte # |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

| Command (hex) |

01 |

4D |

00 |

00 |

01 |

FF |

FF |

FF |

FF |

| Data (hex) |

FF |

F3 |

5A |

00 |

01 |

FF |

FF |

FF |

FF |

| section |

header |

config parameters |

— 0x4F Config controller to return all pressure values

| byte # |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

| Command (hex) |

01 |

4F |

00 |

FF |

FF |

03 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

| Data (hex) |

FF |

F3 |

5A |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

5A |

| section |

header |

config parameters |

— 0x43 Exit config mode

| byte # |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

| Command (hex) |

01 |

43 |

00 |

0x00 |

5A |

5A |

5A |

5A |

5A |

| Data (hex) |

FF |

F3 |

5A |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

| section |

header |

config parameters |

— 0x42 Example Poll (loop this)

| byte # |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

21 |

| Command (hex) |

01 |

42 |

00 |

WW |

YY |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

| Data (hex) |

FF |

79 |

5A |

FF |

FF |

7F |

7F |

7F |

7F |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

| section |

header |

digital |

analog joy |

button pressures (0xFF = fully pressed) |

| analog map |

|

RX |

RY |

LX |

LY |

R |

L |

U |

D |

Tri |

O |

X |

Sqr |

L1 |

R1 |

L2 |

R2 |

Hand-shaking (first communication) recordings between Play Station 2 and Various Controllers

This excel sheet lists both the commands and response data between a play station and various controllers when the controller is first plugged in. Includes guitar hero, dual shock, wire less katana and chinese knock-off (looks the same as the dual shock).

Both a guitar hero game and dirt-bike game (to get vibration motor control data) were used.

We used 2 PIC18f4550 to do the port sniffing, see below to download the code.

PIC18f4550 Code to Read a PlayStation 2 Dual Shock or Guitar Hero Controller

The first program will configure a controller in analog mode so that all the joysticks and button pressures can be read. It also sets up the Left pressure to controller the left vibration motor and the Right button pressure to toggle the smaller right vibration motor.

Each command and response packet is sent out a serial port at 57600 kbs.

ps2_commander_reader.zip

The second program can operate in two modes:

- Continous SPI to Serial: Every SPI byte is sent out the serial port at 57600. Since the play station communicates at 512kbs, the code uses a circular buffer to capture SPI bytes until the playstation pauses between packets, at which time it sends out the data via serial.

- Bulk Capture and Dump: Caputer about 650 bytes of data into buffers, then dump the entire batch out through serial. We used this code to capture the initial communication between a Play Station and controller when they first connect. There are probably about 100 cleaner ways to do this, but the PICs we had on hand only had one SPI port, so two PICs were used at the same time to capture both the command and data lines. One PIC would send back it’s recordings immediately, and the other would wait for a few seconds, during which time a switch was flipped to connect the PC’s serial to the 2nd PIC.

ps2_listener.zip

Connection Schematic:

note: avoid connecting the PIC’s SPI clock to a play station’s clock when the PIC is configured as a SPI master.

Click “Export to Schematic” to place the component.

Click “Export to Schematic” to place the component.

You can also add power or ground connections using the Library Browser and normal Add Parts button–the Add Power button is a shortcut to the Power library.

You can also add power or ground connections using the Library Browser and normal Add Parts button–the Add Power button is a shortcut to the Power library.

Feedback and corrections are greatly appreciated.

I can only get the first half of the video to play

sometimes the video can take a while to load—try reloading the page. A slightly lower resolution version of the how to solder video can be seen at YouTube.

great vid, very helpful!

Thank you for this video !!! Helped me out a lot !!! Really appreciate it !!

I have always had trouble getting good solder joints and to get solder to adhere on wire. Thank You for a very informative easy to understand Video and Narration.

cool!

sigh Remember people that lead is still by far the worse problem here. It takes about 8-15 micrograms (micro, not a mistake and I’ve thoroughly checked that) ingested per day to cause “lead poisoning” in a 6-year old. That means at least “special education” for Timmy, and it’s comparably bad for adults on a /kg basis. Just be smart and use lead-free. It’s a no-brainer for those who know the facts involved.

egads, I just watched the video. The way he is cleaning the solder tip, etc… When it’s sitting on a joint or used with prudence it’s one thing…. even intact solder will release lead oxide (a readily distributable powder) for a variety of reasons, and if you’re going to step on it, allow to oxidize under heat …. sand! Parts usually are pre-tinned with lead alloys. BAD IDEA…. look, using lead solder is a bad idea, okay. Don’t.

it’s illegal to use lead solder in plumbing, but the amount you’d get on your hands from doing these things here could be thousands of times what would leach out of solder joints into water you drink. True, I don’t know how much gets ingested from what’s on your hands, table feet floor, but we clearly have a problem here. It would be most interesting to try an experiment with an appropriate amount of bitrex on the surface of all the solder, and see if you notice how you end up ingesting it eventually – that would demonstrate how you cannot keep the lead in one place if you use it like this.

The hobbyist should be the last to use lead solder, and yet many in industry have already stopped. I’m not talking about “the environment”, I’m talking about not harming yourself and your household. Just think for a second the sort of concentrations we’re talking about in a landfill vs. your house. If having lead around matters in a landfill, it should matter in your house. Why am I writing this, apparently with some ulterior motive? Because I’ve seen how bad lead is, and I don’t want to have to put up with somebody else’s mess. Lead is so hard to clean up and easy to not put down, it’s time to grow up and start being a bit more responsible about it.

I hardly object to it’s use in SLA batteries for instance, but this is not it’s place.

While it’s certainly a good idea to wash your hands after soldering with lead-based solder, I’m not convinced that there’s significant risk to using lead-based solder. Sure, ingesting small amounts can be harmful, but how likely is it that small amounts wil actually be ingested?

Lead-free solder has its risks, too….

This claims there is evidence that the fumes from lead-free solder are more harmful (just how much more harmful? not sure…)

The lead-free alternatives have environmental costs as well.

It would be interesting to find out just how much lead from hand-soldering becomes ingested on average. I suspect it’s not a harmful amount. Assembly line workers have been assembling equipment with lead-based solder for a couple decades now, and I haven’t been able to find any studies showing a harmful amount of ingestion, although there are many that discuss the asthma risks from the flux fumes. (see this OKi ad)

Some more food for thought: this

article claims that there have actually been no documented studies showing ground water contamination from lead in land-fills (the main impetus for RoHS and WEEE regulations). Apparently lead from electronics comprises less than 1% of lead used, the rest coming mainly from batteries and CRT monitors (although the disposal of these is much more controlled). Note, lead can in fact be leached from PCBs, so I’m definitely not arguing against the prudence of those regulations.

I’d be very grateful for links to studies showing documented cases of lead-poisoning from hand-soldering.

excellent video – clear and to the point – great work.

Thanks a million. That video is a huge help. Very well done.

@scott: I’d highly suggest you watch Manufactured Landscape which has nothing to do with this except for one part where he goes to villages in China known for recycling electronics and noticed that you can smell the heavy metals from miles away and that the government now has to deliver water by truck as the natural sources are all contaminated.

point taken 🙂 If you have a link to youtube that’d be great…

I wonder what all is being thrown into that particular village… a lot of lead is used in car batteries here in the States, but their recycling is very much controlled, so little battery lead ends up in land fills.

Sounds like that village missed out on China’s version of RoHS.

why pronounce it “sawder”? Took me ages to work out what he was on about.

same reason it’s spelled “could” and sounds like “kude”

Outstanding video! I will be building a kit soon, and I found the information in the film will be of great help. Thanks so very much.

Dick Williams KB3OMJ

A good tutorial. I’ve been soldering for over 20 years (professionally and hobbyist), but it’s always good to brush up on techniques.

thanks… we’d love to hear any critiques you have or better ways of doing things that you’ve picked up over the years.

In further answer to the March 12, 2008 question “why pronounce it “sawder”? Took me ages to work out what he was on about,” please note that the questioner is not a native American english speaker, but rather a United Kingdom native speaker, wherever he/she actually resides. The North American pronunciation of “solder” is indeed “sawder.” But I would also point out that the phrase “he was on about” is equally obscure on this continent. It is not used here, except by those trying to emulate usage in Great Britain and its commonwealth. I would suggest that the original poster not be so critical, particularly while revealing his own linguistic shortcomings and lack of exposure to the usages of English around the world. The other commentator was a bit more cryptic, if more humorous than I, when he said “same reason it’s spelled “could” and sounds like “kude”. And finally, no less a personage than Sir Winston Churchill said something to the effect that “the UK & USA were two countries divided by the same language.” It was a good joke when he said it, and all the more so because it was so true, both then and now.

Now on to more important things. After all that, I will add that I thought the video was very well done, and will recommend it to a number of people with whom I work who will profit a great deal by it. I have been occasionally soldering electronic components for over 55 years now, and while I can recognize both bad and good solder joints, I have not been able to convey that knowledge to those 1/3 my age in nearly so clear a form as this video. Good work, and many thanks.

thanks!

And now for something completely different.

The online etymological dictionary says:

https://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=solder

As for the snippish comment about “could”:

https://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=could

Great Video! I’m just starting to get into some of this for repairing/modding old video game systems, to make them into musical devices and this gives me hope that with time I can start to understand the process enough not to mess it up.

I just broke the piece of metal on my glasses that connects the two lenses together and I was wondering if that was something that would be able to be soldered? I also have a 1 year old that loves grabbing at them so I would assume lead based solder wire would not be a good idea, any advice?

Hey, does anyone know what solder and devices would be needed for a newbie to desolder and resolder the audio wires for a nintendo ds lite??

I need it for no other purpose than that

please post questions in our soldering forum

thanks!

wow everything you said not to do I’ve done so this video is GREATLY apprieciated thank you!!!

This must be the best Tut Vid i have seen online !!

Tip requires sanding as the solder alloys with the copper of the tip forming brass. Brass has different solderability (wettability + thermal conductivity) than original high copper tip. Section a tip and metallographically prepare and etch it and it is readily apparant we are dealing with two metallurgically distinct regions. Sanding (grinding) is the solution .. excessive tinning might be the problem (along with excessive heat) under no-load conditions.

Spock out!

Very good vid. I especially like how you show bad examples, as well as good – that’s missing from other training videos I’ve seen.

And thanks too for tempering the OMG-Lead-We’re-Gonna-Die hysteria. Good links and rational info provided on the subject. I searched once trying to find the vapor pressure of lead at soldering temperatures. No luck except for one paper that had measured it at higher temps and extrapolated the result to soldering temps, describing it as: ‘a really hard vacuum’. The only other thing I’ve found are reports of no elevated blood levels of lead in electronics workers after years of ‘exposure’.

I’ve also read of the poor children in the contaminated ‘recycling villages’ in China (and elsewhere). If they weren’t being exposed to the tiny bit of lead in electronics, they will certainly be exposed to the much greater amount of lead in CRT’s and batteries. It’s

alldone illegally anyway, and if it’s not lead it’ll be something else that’s toxic, illegal, and profitable, that someone will use to expolit people at that level in that type of society. Removing lead in electronics is “not” a solution to that problem.Thanks for the video. I’ve done a little electronics soldering here and there over the last 20 years or so, and I’ve honestly never really had a clue what I was doing. This video was much more helpful than reading about it in a book.

Thanks a lot, this was a great help, I had done larger scale stuff, like pipes, but that’s a total different ball game.

Very good, just one suggestion: speak a little slower. Thank you!

great tutorial for someone who knows nothing from soldering

Excellent guide! Very useful.

i hoped to see this video moths ago, i reallly did a mess in my pcb projects, so now that i know how soldering, i will try hard to make a better work, thanks a lot ^^

I have done NASA certified soldering, and you have shown excellent views of good and bad joints. We used soft erasers to clean board pads and componant leads. Gold pads were more difficult to achieve a good shiny flow.

Great video, it’s all more clear now 🙂 Thank you.

This is the best how to solder video I’ve seen yet, and I’ve been looking at many. You explained the technique as well as the chemistry behind the process, and had good repetitive video samples. I had never heard of the heat bridge and soldering from the opposite side of the wire. Thanks a billion!